The State of North Carolina is at a critical turning point for the future impacts of fracking on public health and the environment. One of the key issues up for comment and debate involves whether or not the public (including doctors and first responders) have the right to know the facts about the toxic chemicals used during fracking. The NC General Assembly has included an unworkable and unethical provision which threatens to impose criminal penalties on anyone who discloses such information.

The State of North Carolina is at a critical turning point for the future impacts of fracking on public health and the environment. One of the key issues up for comment and debate involves whether or not the public (including doctors and first responders) have the right to know the facts about the toxic chemicals used during fracking. The NC General Assembly has included an unworkable and unethical provision which threatens to impose criminal penalties on anyone who discloses such information.

Fortunately, there area number of credible and publicly available sources of information about the 600 chemicals currently contained in fracking fluid. The most important of these was published by the US House of Representatives Committee on Energy in April 2011. You will find the executive summary and a link to the full report if you continue reading. The main point is that fracking fluid is risky and unregulated. Read here about the main toxic chemicals that routinely are discovered in water supplies where fracking occurs. Even without knowing the trade secrets Halliburton and others want to keep – the evidence is clear that the State of North Carolina should reject fracking!

Click below to learn what hazardous chemicals are widely known to be in fracking fluid.

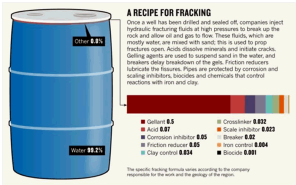

What’s in fracking fluid?

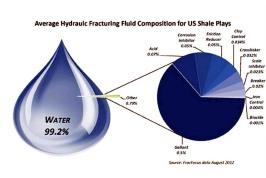

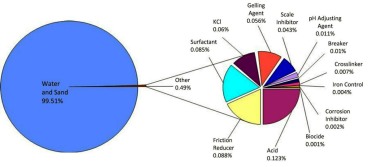

Fracking fluid is a toxic brew that consists of multiple chemicals. Industry can pick from a menu of up to 600 different kinds. Typically, 5 to 10 chemicals are used in a single frack job, but a well can be fracked multiple times, and each gas play consists of tens to hundreds of thousands of wells – driving up the number of chemicals ultimately used. Many fracking chemicals are protected from disclosure under trade secret exemptions. Studies of fracking waste have identified formaldehyde, acetic acids, and boric acids, among hundreds of others.

For each frack, 80-300 tons of chemicals may be used, selected from a menu of up to 600 “different” chemicals. Though the composition of most fracking chemicals remains protected from disclosure through various “trade secret” exemptions under state or federal law, scientists analyzing fracked fluid have identified volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene – all of which pose significant dangers to human health and welfare.

What Chemicals Are Used

As previously noted, chemicals perform many functions in a hydraulic fracturing job. Although there are dozens to hundreds of chemicals which could be used as additives, there are a limited number which are routinely used in hydraulic fracturing. This website provides a list of the chemicals used most often. This chart is sorted alphabetically by the Product Function to make it easier for you to compare to the fracturing records.

List of additives for hydraulic fracturing From Wikipedia

In the United States, about 750 compounds have been listed as additives for hydraulic fracturing in a report to the US Congress in 2011 after originally being kept secret for “commercial reasons”. The following is a partial list of the chemical constituents in additives that are used or have been used in fracturing operations, as based on the report of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, some are known to be carcinogenic. In the UK only ‘Non-Hazardous’ chemicals are permitted for fracturing fluids by the Environment Agency. All chemicals have to be declared publicly and, increasingly, food additive based chemicals are available to allow fracking to take place safely.

NC fracking panel passes chemical disclosure rule By John Murawski – January 14, 2014

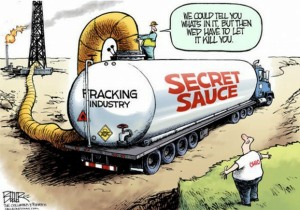

Fracking companies won the right to keep secret the chemical cocktails they pump underground during shale gas drilling in North Carolina under a chemical disclosure rule approved Tuesday by the N.C. Mining and Energy Commission. The public safety standard will help the energy companies protect their secret sauce used in natural gas drilling, but critics said it would also keep residents in the dark about potent chemicals used near local farms and waterways.

The rule passed unanimously after nearly three hours of intense debate Tuesday, and it follows more than a year of deliberations that had the commissioners tied up in knots. Commissioners sought to appease frightened residents, the energy industry and lawmakers eager to promote drilling for economic development.

The rule as passed by the commission is merely a recommendation to the state legislature, which will have final say over fracking standards later this year or next year. But as it now stands, the rule puts North Carolina among the states that don’t require energy exploration companies to turn over corporate trade secrets to government agencies for safeguarding in case of emergency. “A lot of folks have heartburn because there are some states that do take possession of the trade secret,” said Commission Chairman James Womack. “We will have safe and responsible drilling in North Carolina.” …

Shale gas exploration is under moratorium in North Carolina as the Mining and Energy Commission races to complete more than 100 regulations to protect the environment and public health. Chemicals are used in fracking to break up shale rock and release trapped gas and prevent pipe corrosion. They do not have to be publicly disclosed under a 2005 congressional exemption to the Safe Drinking Water Act, prompting states to come up with their own standards. The chemicals range from household cleansers to food additives and industrial solvents.

North Carolina’s rule, if approved by lawmakers, will require that any trade secret claim be reviewed by the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. The review process has not been created but would require a sworn statement from the company that the trade secret has not been publicly disclosed elsewhere. “The rule requires that permitees provide relatively detailed justifications when they claim trade secrets,” said Hannah Wiseman, a law professor at Florida State University who studies fracking regulations across the country.

Operators at a drill site are required by federal law to keep a safety sheet detailing chemicals used on that site; they are also required to turn over the data to public officials during a spill or accident. But getting the same data off-site is more complicated. Such a request would be handled by calling a 24-hour phone number, to be staffed by the energy company, as called for by North Carolina’s rule. The company would have two hours to disclose the information to medical professionals and emergency responders, but it’s not clear how the company would validate that the request is legitimate and authorized.

Many have criticized this process as unworkable, especially if residents complained of polluted water or delayed symptoms long after the company and its contractors had left the state. “An individual can be sick, hospitalized, drunk or have the phone off the hook,” John Wagner, a Chatham County resident, told the commission. “Access means full and immediate access, not access to material at the office, or in a safety deposit box that is available on the next business day.”

Chemicals shielded as trade secrets are commonly known by chemists and scientists, so the only issue is which chemicals a company is using in its mixture, and in what combinations. “The secrecy thing is to me a joke,” said Commissioner Vikram Rao, a former chief technology officer for energy conglomerate Halliburton. “The secret, such as it is, is only of value to the competitor.”

North Carolina GOP Pushes Unprecedented Bill to Jail Anyone Who Discloses Fracking Chemicals by Molly Redden – May 31, 2014

As hydraulic fracturing ramps up around the country, so do concerns about its health impacts. These concerns have led 20 states to require the disclosure of industrial chemicals used in the fracking process. North Carolina isn’t on that list of states yet — and it may be hurtling in the opposite direction.

On Thursday, three Republican state senators introduced a bill that would slap a felony charge on individuals who disclosed confidential information about fracking chemicals. The bill, whose sponsors include a member of Republican party leadership, establishes procedures for fire chiefs and health care providers to obtain chemical information during emergencies. But as the trade publication Energywire noted Friday, individuals who leak information outside of emergency settings could be penalized with fines and several months in prison.

“The felony provision is far stricter than most states’ provisions in terms of the penalty for violating trade secrets,” says Hannah Wiseman, a Florida State University assistant law professor who studies fracking regulations. The bill also allows companies that own the chemical information to require emergency responders to sign a confidentiality agreement. And it’s not clear what the penalty would be for a health care worker or fire chief who spoke about their experiences with chemical accidents to colleagues.

“I think the only penalties to fire chiefs and doctors, if they talked about it at their annual conference, would be the penalties contained in the confidentiality agreement,” says Wiseman. “But [the bill] is so poorly worded, I cannot confirm that if an emergency responder or fire chief discloses that confidential information, they too would not be subject to a felony.” In some sections, she says, “That appears to be the case.”

The disclosure of the chemicals used to break up shale formations and release natural gas is one of the most heated issues surrounding fracking. Many energy companies argue that the information should be proprietary, while public health advocates counter that they can’t monitor for environmental and health impacts without it. Under public pressure, a few companies have begun to report chemicals voluntarily.

Chemicals Used in Fracking

Fracking fluids are complex mixtures of chemicals, water, and sand that are unique to each company. Like Colonel Sanders’ 11 secret herbs and spices, the makeup of this fluid is a jealously guarded trade secret that the oil and gas companies typically refuse to divulge, even under pressure. In the past, the industry has remained largely unregulated, but over the last few years, environmental watchdog groups have become increasingly concerned.

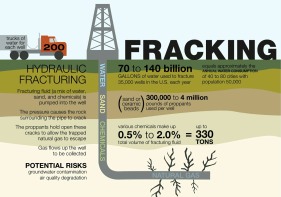

Contrary to the image most of us may envision, of vast pools of oil deep within the earth that merely need to be tapped and sucked out, most oil and gas is found in small pockets of rock. Far beneath the Earth’s surface lie multiple layers of different materials, including shale and clay. These porous rock formations trap natural gas, making it difficult to extract these fuels. Drilling companies use high pressure water, chemicals, and sand to create cracks in the rocks, allowing the gas to escape and flow towards the wells, where it can be collected and processed for sale. This process is known as “fracking,” which is shorthand for hydraulic fracturing.

It takes a great deal of pressure and a lot of liquid to crack the rock layer buried thousands of feet underground. Approximately 90% of all gas wells located on land employ fracking as a means of making gas more accessible. Most wells are fracked numerous times to extract the maximum profit from a drilling site before the well is exhausted.

Between 50,000 and 350,000 gallons of fluid are used during a fracking treatment, plus 75,000 to 320,000 pounds of sand, or proppant. The sand fills the cracks left by the pressurized liquid to keep the cracks from closing during the oil extraction process.

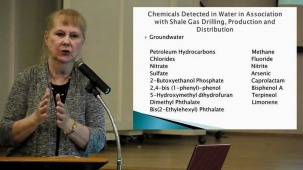

Since the rock layer is porous, water alone cannot be used as fracking fluid. Water would simply sink into the rock without cracking the substrate. For this reason, the drilling companies must make a slick mixture of fracking fluids. Hundreds of chemicals may go into the mix, including many cancer-causing agents and chemicals known to be toxic to humans, animals, and the environment. While oil and gas corporations fight legally to avoid releasing the ingredients in this toxic stew, scientists researching the problem have analyzed fracking fluid and discovered the following substances common to diesel fuel: BULLETTS

- Benzene

- Ethylbenzene

- Toluene

- Xylene

- Naphthalene

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- Methanol

- Formaldehyde

- Ethylene glycol

- Glycol ethers

- Hydrochloric acid

- Sodium hydroxide

Not all companies use diesel fuel, but most of the companies surveyed by a 2010 congressional committee admitted that diesel fuel is part of their fracking mixture. Even in cases where diesel fuel is not used, the mixture generally includes high levels of benzene. It takes only a tiny amount of benzene to poison millions of gallons of groundwater. In the five years studied by the investigation (2005 to 2009), 32 million gallons of hydraulic fluids have been pumped into the ground in the United States. None of the companies that admitted using diesel fuel in their fracking mixture requested or acquired a permit to use diesel fuel as required by law.

Fracking Chemicals Cited in Congressional Report Stay Underground by Nicholas Kusnetz, April 18, 2011

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD CONGRESSIONAL REPORT (PDF)

A report released Saturday confirmed details about what many already knew was happening: gas drillers have injected millions of gallons of fluids containing toxic or carcinogenic chemicals into the ground in recent years. The report, by congressional Democrats, lists 750 chemicals and compounds used by 14 oil and gas service companies from 2005 to 2009 to help extract natural gas from the ground in a process called hydraulic fracturing.

That list includes 29 chemicals that are either known or possible carcinogens or are regulated by the federal government because of other risks to human health. As we reported more than a year ago, most of the fluids now used in hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” are left underground when drilling ends. The report notes that while the fate of these fluids “is not entirely predictable,” in most cases, “the permanent underground injection of chemicals used for hydraulic fracturing is not regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency.”

The amount of fluid that remains in a well varies depending on local geology. But in some states, including Texas and Pennsylvania, regulators do not know precisely how much of the fluid returns to the surface for each well. In many cases, particularly in the Marcellus Shale in the Northeast, more than three-quarters of the fluid is left underground.

In 2005, Congress exempted hydraulic fracturing from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. That law allows the EPA to regulate the injection of hazardous fluids into underground wells, a practice widely used to dispose of drilling wastewater. As we wrote back in 2009:

If another industry proposed injecting chemicals — or even salt water — underground for disposal, the EPA would require it to conduct a geological study to make sure the ground could hold those fluids without leaking and to follow construction standards when building the well. In some cases the EPA would also establish a monitoring system to track what happened as the well-aged.”

But the oil and gas industry lobbied to protect fracking from such regulation, arguing that most of the fluid remains underground only temporarily. Stephanie Meadows, then a senior policy analyst for the American Petroleum Institute, told us in 2009 that, “Hydraulic fracturing operations are something that are done from 24 hours to a couple of days versus a program where you are injecting products into the ground and they are intended to be sequestered for time into the future.”

When they approved the Safe Drinking Water Act exemption, lawmakers believed only about 30 percent of the fluids remained underground. Subsequent reports and interviews with drillers show the amount can reach 80 percent or higher. The Democrats’ report, which provides the most comprehensive list of the chemicals used to frack natural gas wells, also highlights ongoing gaps in knowledge. It says drillers injected 94 million gallons of fluid — about 12 percent of the total amount used over the five years — containing at least one chemical deemed a trade secret.

“In most cases the companies stated that they did not have access to proprietary information about products they purchased ‘off the shelf’ from chemical suppliers,” the report says. “In these cases, the companies are injecting fluids containing chemicals that they themselves cannot identify.” Much is still unknown about what happens to that fluid when it’s left inside the well, or whether it threatens drinking water. …

The report is the product of an investigation into hydraulic fracturing by Reps. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., Edward Markey, D-Mass., and Diana DeGette, D-Colo. In January, they released a report showing that the same 14 drilling companies had used more than 32 million gallons of diesel fuel or fluids containing diesel in fracking operations.

UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE – APRIL 2011

CHEMICALS USED IN HYDRAULIC FRACTURING

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Hydraulic fracturing has helped to expand natural gas production in the United States, unlocking large natural gas supplies in shale and other unconventional formations across the country. As a result of hydraulic fracturing and advances in horizontal drilling technology, natural gas production in 2010 reached the highest level in decades. According to new estimates by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), the United States possesses natural gas resources sufficient to supply the United States for approximately 110 years.

As the use of hydraulic fracturing has grown, so have concerns about its environmental and public health impacts. One concern is that hydraulic fracturing fluids used to fracture rock formations contain numerous chemicals that could harm human health and the environment, especially if they enter drinking water supplies. The opposition of many oil and gas companies to public disclosure of the chemicals they use has compounded this concern.

Last Congress, the Committee on Energy and Commerce launched an investigation to examine the practice of hydraulic fracturing in the United States. As part of that inquiry, the Committee asked the 14 leading oil and gas service companies to disclose the types and volumes of the hydraulic fracturing products they used in their fluids between 2005 and 2009 and the chemical contents of those products. This report summarizes the information provided to the Committee.

Between 2005 and 2009, the 14 oil and gas service companies used more than 2,500 hydraulic fracturing products containing 750 chemicals and other components. Overall, these companies used 780 million gallons of hydraulic fracturing products – not including water added at the well site – between 2005 and 2009.

Some of the components used in the hydraulic fracturing products were common and generally harmless, such as salt and citric acid. Some were unexpected, such as instant coffee and walnut hulls. And some were extremely toxic, such as benzene and lead. Appendix A lists each of the 750 chemicals and other components used in hydraulic fracturing products between 2005 and 2009.

The most widely used chemical in hydraulic fracturing during this time period, as measured by the number of compounds containing the chemical, was methanol. Methanol, which was used in 342 hydraulic fracturing products, is a hazardous air pollutant and is on the candidate list for potential regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Some of the other most widely used chemicals were isopropyl alcohol (used in 274 products), 2-butoxyethanol (used in 126 products), and ethylene glycol (used in 119 products).

Between 2005 and 2009, the oil and gas service companies used hydraulic fracturing products containing 29 chemicals that are (1) known or possible human carcinogens, (2) regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act for their risks to human health, or (3) listed as hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act. These 29 chemicals were components of more than 650 different products used in hydraulic fracturing.

Halliburton Fracking Spill Mystery: What Chemicals Polluted an Ohio Waterway? By Mariah Blake – Jul. 24, 2014

A recent accident highlights how state fracking laws protect corporate trade secrets over public safety. On the morning of June 28, a fire broke out at a Halliburton fracking site in Monroe County, Ohio. As flames engulfed the area, trucks began exploding and thousands of gallons of toxic chemicals spilled into a tributary of the Ohio River, which supplies drinking water for millions of residents. More than 70,000 fish died. Nevertheless, it took five days for the Environmental Protection Agency and its Ohio counterpart to get a full list of the chemicals polluting the waterway. “We knew there was something toxic in the water,” says an environmental official who was on the scene. “But we had no way of assessing whether it was a threat to human health or how best to protect the public.”

This episode highlights a glaring gap in fracking safety standards. In Ohio, as in most other states, fracking companies are allowed to withhold some information about the chemical stew they pump into the ground to break up rocks and release trapped natural gas. The oil and gas industry and its allies at the American Legislative exchange Council (ALEC), a pro-business outfit that has played a major role in shaping fracking regulation, argue that the formulas are trade secrets that merit protection. But environmental groups say the lack of transparency makes it difficult to track fracking-related drinking water contamination and can hobble the government response to emergencies, such as the Halliburton spill in Ohio.

According to a preliminary EPA inquiry, more than 25,000 gallons of chemicals, diesel fuel, and other compounds were released during the accident, which began with a ruptured hydraulic line spraying flammable liquid on hot equipment. The flames later engulfed 20 trucks, triggering some 30 explosions that rained shrapnel over the site and hampered firefighting efforts.

Officials from the EPA, the Ohio EPA, and the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) arrived on the scene shortly after the fire erupted. Working with an outside firm hired by Statoil, the site’s owner, they immediately began testing water for contaminates. They found a number of toxic chemicals, including ethylene glycol, which can damage kidneys, and phthalates, which are linked to a raft of grave health problems. Soon dead fish began surfacing downstream from the spill. Nathan Johnson, a staff attorney for the non-profit Ohio Environmental Council, describes the scene as “a miles-long trail of death and destruction” with tens of thousands of fish floating belly up.

Statoil and the federal and state officials set up a “unified command” center and began scouring a list of chemicals Halliburton had provided them for a compound that might be triggering the die off. But the company had not disclosed those ingredients that it considered trade secrets. Halliburton was under no obligation to reveal the full roster of chemicals. Under a 2012 Ohio law — which includes key provisions from ALEC’s model bill on fracking fluid disclosure — gas drillers are legally required to reveal some of the chemicals they use, but only 60 days after a fracking job is finished. And they don’t have to disclose proprietary ingredients, except in emergencies.